AI Might Make Long Specs Cool Again

Despite all the challenges in maintaining them

Key takeaways

AI needs precise specifications to generate code/tests. Otherwise, well… guess!

Useful software is complex: it has an incredibly large number of unique states, making it hard to describe and test. It’s in its nature. There's no silver bullet.

We used to write long specs in the waterfall era. But it was so painful that we collectively decided to quit.

Detailed spec docs are painful to read and write. And code is just as bad.

The future: IDEs for specs instead of code? Maybe. How do you give specs to AI?

AI Requires Detailed Specs To Generate Good Code and Tests (or, guess…)

Imagine you tell an LLM: “write me an e-commerce site to sell clothes”. The LLM scrambles among its vast database of websites, code, books, videos, posts and memes to give you a good response. It doesn’t know exactly what you want, so it wings it with something like:

Guess requirements: Products, categories, orders, cart, auth. The common stuff in e-commerce systems.

Pick a popular stack: React, Node/Python, Postgres. The most popular stuff in its database.

Generate code: It spits out a simple DB schema, a backend and a frontend. It tries to make it compile.

Iterate: It pokes the code until it stops crashing.

It’s impressive. It often works at first shot and looks prettier than you expected. It makes you feel good. It makes you forget that it guessed your specification gaps with the statistical average of the internet.

But it guessed… a lot. Sometimes the outcome of a guess will be great. Sometimes it’ll be wrong. That’s just the nature of a guess. Even well informed ones.

For the guesses that went wrong, you can always iterate: “Change [this]. Add [that]”. But if you played this game a few times, you know that AI will eventually drift off – just like your partner when you’re talking about your day at work. After enough iterations AI will start paying less attention to important details. And your context will accumulate a lot of irrelevant details.

For the LLM to do a better job, your prompt needs to be accurate and complete. In general, the smaller the “distance” between your input and the expected output, the better the output. Because when context has very specific details, the LLM doesn’t need to guess much.

But the truth is: software is inherently complex. Writing an unambiguous list of requirements is hard and painful – especially upfront.

Simple Systems Are a Myth

As Bjarne Stroustrup (creator of C++) noted: “Hardly any useful program is trivial“.

In the real world, systems that are apparently simple, get complicated very quickly. A prompt with “An e-commerce to sell clothes online” – sounds simple. But it only sounds reasonable until some smarty-pants comes asking those annoying questions, like:

Are you offering loyalty points? Personal recommendations? How does that all work?

Does adding an item to cart reserve the item?

If yes, one can break your store by adding everything to their cart and not buying anything.

If no, two people buy the last shirt at the exact same second. Who gets it?

Does the 10% off before or after the $20 voucher? The answer changes the price. Your CFO cares.

AI can guess answers to those questions. But often there are no generic correct answers to those types of questions. They require you to make choices and these choices will have trade-offs. And writing down these choices, will inevitably become a long, complicated and boring specification.

Frederick Brooks articulated the irreducibility of software complexity in his paper No Silver Bullets (from 1987!) , very eloquently. So I'll quote:

“There is no single development, in either technology or in management technique, that by itself promises even one order-of-magnitude improvement in productivity, in reliability, in simplicity.

[...]

Digital computers are themselves more complex than most things people build: They have very large numbers of states. This makes conceiving, describing, and testing them hard. Software systems have orders-of-magnitude more states than computers do.

Likewise, a scaling-up of a software entity is not merely a repetition of the same elements in larger sizes, it is necessarily an increase in the number of different elements. In most cases, the elements interact with each other in some nonlinear fashion, and the complexity of the whole increases much more than linearly.

The complexity of software is an essential property, not an accidental one. Hence, descriptions of a software entity that abstract away its complexity often abstract away its essence. For three centuries, mathematics and the physical sciences made great strides by constructing simplified models of complex phenomena, deriving properties from the models, and verifying those properties by experiment. This paradigm worked because the complexities ignored in the models were not the essential properties of the phenomena. It does not work when the complexities are the essence.”

Many years (and technologies) later, Brooks’ point seems to stand. Productivity gains in software engineering remain modest. There’s some hope that AI will change that, but we’re still to see a 10x increase in productivity across the board in software engineering.

Is AI gonna be our productivity silver bullet? Well, can you specify what you want (and get AI to guess what you didn’t), and make it generate exactly what you want 10x faster than you can write code? I suspect that’s quickly becoming true for an increasing number of people, especially for new/small systems. But as the code becomes larger and more complex, that gain in productivity seems to drop greatly. I suspect that’s mostly due to two things:

Poor context management, which the best models are quickly improving.

The lack of precision specifying what’s required from AI. This seems to be much harder to "just guess". Guesses at scale compound errors.

I suspect that although LLMs will continue to improve at guessing what’s omitted, the specification problem will remain essential. To solve problem #2, you’ll need to at least “steer” the spec. Because at the end of the day, AI must know (or correctly guess) exactly what you want the system to do. That’s especially true if we hope for a future where we have hyper-personalized systems that adapt to us, instead of us adapting to them.

A Brief History of… Failure

Back when I was at uni (ahem, around 20 years ago), in the software engineering classes we were taught the (infamous) waterfall method, where software was built like bridges. First we’d study the context and problems to be solved, then plan and design a solution, to only then jump into implementing it.

We wrote functional and non-functional requirements. We drew UML diagrams until our eyes bled. We specified class hierarchies for systems that didn’t exist yet. We used IBM Rational Rose. We felt very professional.

I distinctively remember when my older brother was at uni, a decade before me. Once he was printing a massive software spec he wrote (probably class work), in one of those old dot matrix printers using fanfold paper. Hours and hours of that printing noise – which sounded like a parrot undergoing an exorcism. It really made me contemplate if life was worth living. I still don’t know how on Earth I ended up also studying software after that.

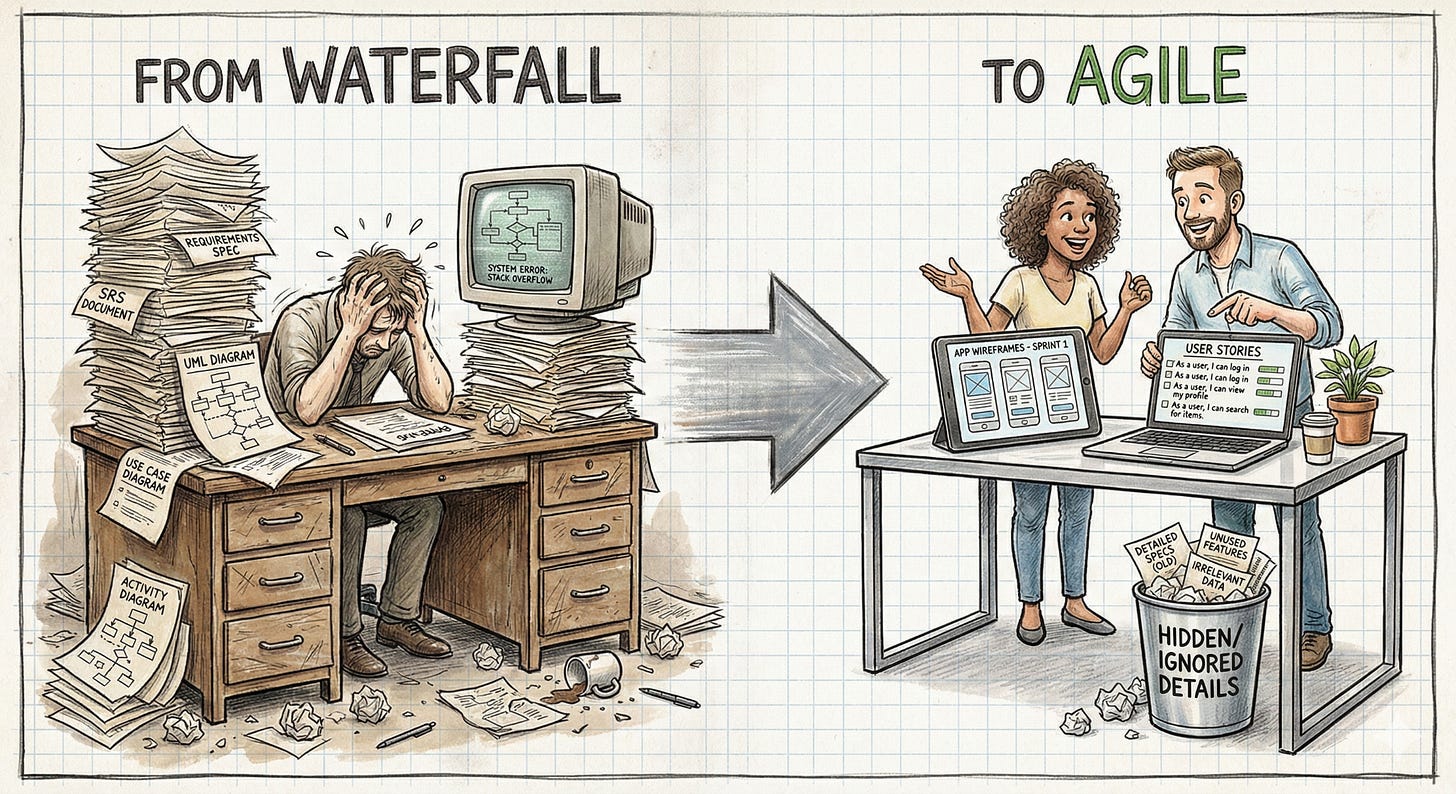

Anyway, back to waterfall: the industry eventually realised that this long discovery and planning process was ineffective. It often took many months. The resulting documentation was a dense and unreadable tome, which often ended up being used as a monitor stand. And the resulting software was often late and expensive. Worse yet, sometimes it didn’t even solve the right problems for its users.

So the software industry gradually pivoted. Enter Agile. The new plan: move fast (sometimes), break things (very often), and think/write less upfront (well, easier). We traded 500-page specs for a bunch of JIRA tickets, full of user-stories and UI designs. We collectively declared that long specification docs were not cool anymore. And behold… it actually worked. Almost every modern software product was built this way.

However the challenge of translating human thought into computer binaries remains. There’s always:

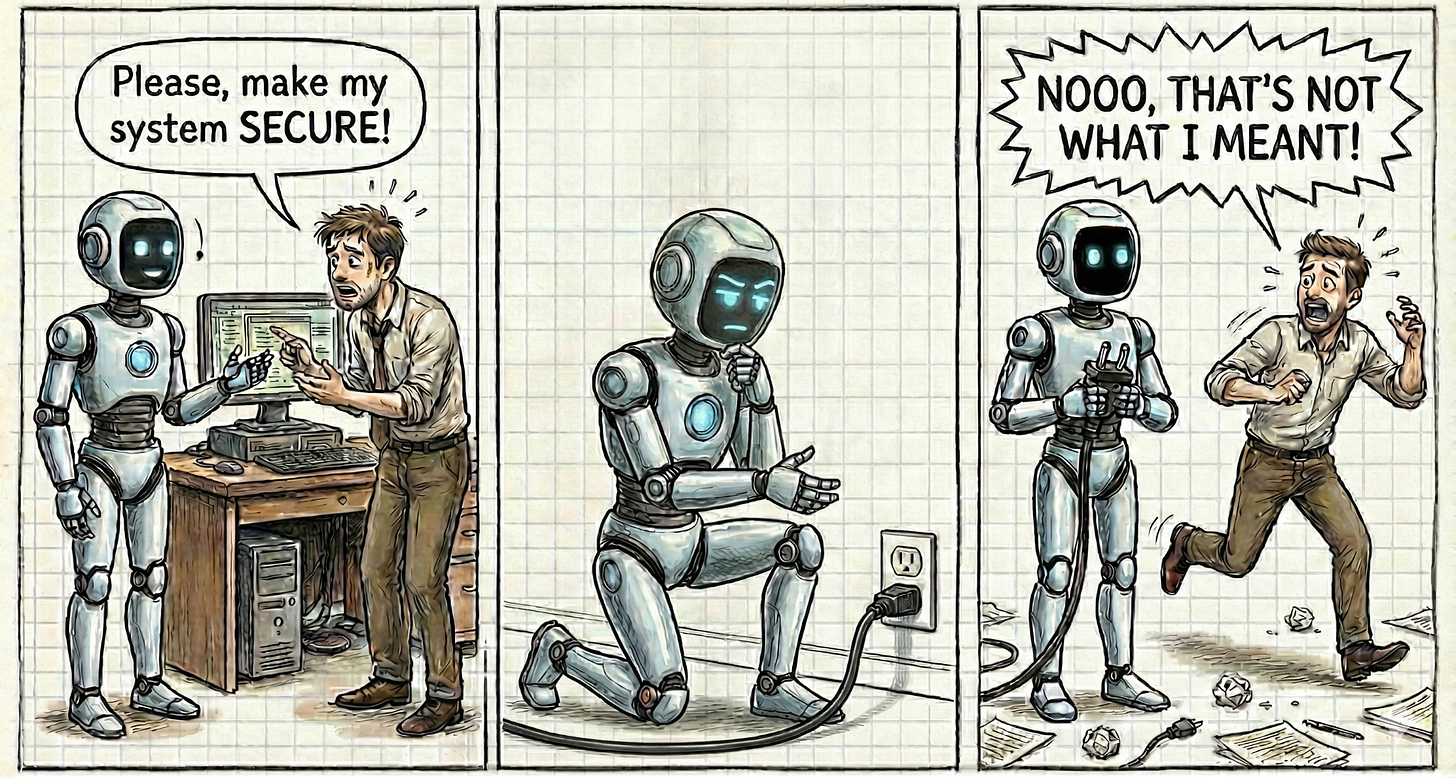

Hidden ambiguity: “Secure login” sounds clear on a piece of paper, until you have to implement it.

Choice and trade-offs: There are many different ways to solve most problems. And each solution brings their own trade-offs.

Unknown unknowns: You don’t know what you need, until you ship the wrong thing.

Spec Artifacts Types and Size Spectrum

There are many ways to write software specifications. We invented a bunch of artifact/document “templates” to aid the process: UML diagrams (use-case, flow, sequence, ERDs, class, etc.), user journeys, mocks, designs, PRDs, RFCs, ADRs, Gherkin given/when/then scenarios, user stories… and the list goes on.

These artifacts are designed to help our limited primate brains to reason about these complex systems, by making us focus on one aspect, while ignoring the rest. Some specification types will remove a lot of details. Some will omit a bit less, but end up a bit longer.

Depending on the amount of details omitted when in these artifacts, the complete system spec size often end up either:

short and vague: apparently nice, but hardly useful – like most politicians’ rhetoric; or

long and dense: exhaustive/complete, but painful to read, write and maintain. The more details it has, the worse it gets. Just like those T&Cs.

Another problem is, computers don’t obey diagrams and JIRA tickets (yet?!). Code is the only thing that the computer obeys. So, wouldn’t code be the most complete and accurate spec?

Well, although many engineers would like to think so, code is also horribly long and dense. Hardly better than those T&Cs. For starters, non-coders can’t read/write it. Second, it can amass tens of thousands of lines, before doing anything really useful. It’s often so dense and subtle, that even your most experienced, sun deprived engineers struggle to review it.

And in terms of AI generation, if the spec is too short, AI will need to guess all the details. And as we’ve seen, it will inevitably be wrong sometimes. But if it’s too long, its attention becomes fuzzy and its output quality drops. So you will need mechanisms to feed AI just what’s really important to the task(s) at hand.

The Future: Maybes of IDEs and Software Specifications

Maybe in the future, IDEs will be a multiplayer game for requirements, instead of a playground only for coders. Maybe writing and managing requirements can be something that doesn’t make you wanna cry. Maybe a single person will be able to understand all the details of a large system, and keep up with it.. Maybe requirements will become the new source code. Maybe…

AI brought a software spec renaissance. Suddenly, specs are cool and necessary again. Specs make it easier to collaborate with non-coders, to visualise and understand complex systems, and are also a great aid to generate and check code that works as expected. We just need to find ways to make them easier to write, read and manage.

ps: I’ve been tinkering with some ideas. I’m not sure if anything useful will come out of it, but I’ll let you know if I make any progress.

In the meanwhile, I’m curious to hear your thoughts: how are you managing the requirements of the code you generate with AI? What are your major pain points?